Giving Birth in Japan

Giving Birth in Japan

Featuring terry robes that make your baby look like the angel he/she is

I previously wrote that the theme of Birth #2 was planning, and if life in Japan is anything, it is conducive to order.

Of course, when talking about healthcare in the US versus other countries, the most discussed aspect is cost. This is definitely important, but I can’t provide a good comparison because I no longer have access to all the US hospital bills from five years ago. I will say giving birth in Japan was expensive, but the hospital was up front about the costs from the beginning, and I see this as a big point of difference between the two countries. Granted, in Japan, I was at a private hospital, where it was understood we would bear the cost of the procedure. (Japanese National Health Insurance can cover a not-insignificant portion of the cost.) Afterward I could, and did, submit the costs to our private insurance company. In a turn that will surprise no one in the US, I have a dispute with part of that reimbursement (to the tune of $1K) that I am still working to resolve nine months later.

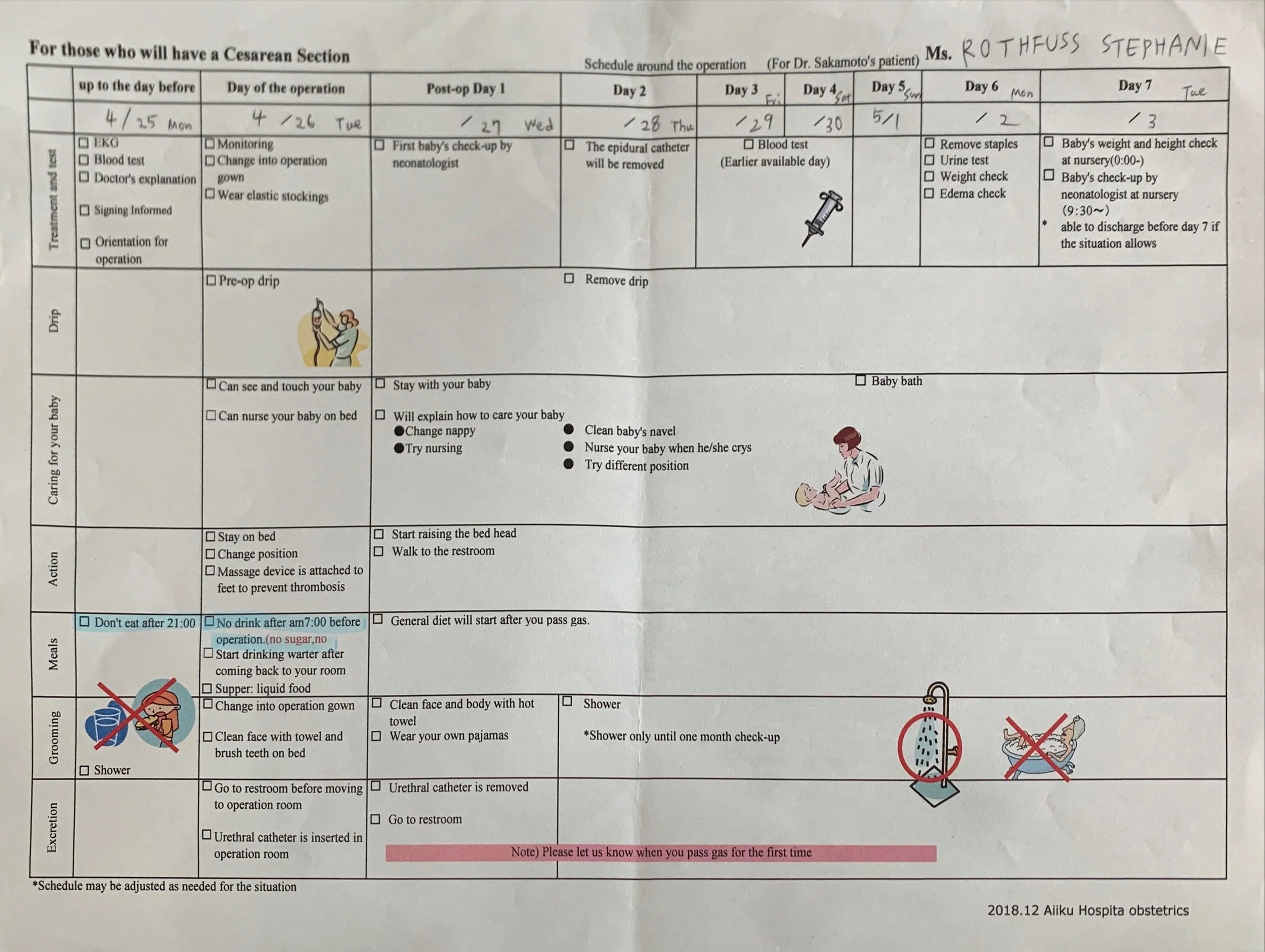

The hospital also provided a schedule ahead of time of what to expect each day I was there. For a cesarean delivery, they allotted one week for delivery and recovery, though my doctor said I could leave after five days if all went well and I felt up to it. I believe the time scheduled for vaginal delivery was also five days. In contrast, a loved one in the US had her first baby in the hospital and was sent home after one night.

The very helpful birth schedule: a progression from post-op recovery to independence

Staying five nights at the hospital (without any visitors, due to the COVID protocols mentioned prior) might sound awful—indeed, when I was in the US hospital with Baby #1, I was begging to leave because I could not rest and felt so miserable. But I actually liked having a longer stay planned, as it was designed for me to regain my independence day by day, and feel ready to leave with Baby.

Day -1

Perhaps one of the more surprising elements of my delivery was checking into the hospital the day before the procedure. An extra night away from home wasn’t a plus, but by that time I was so uncomfortable and tired of being pregnant that being in the hospital the day before felt blissfully one step closer to having the baby. It also helped with the incessant worrying my HELLP would reoccur.

And it didn’t! But I had to stop taking the baby aspirin a few weeks before the delivery date, and my blood pressure skyrocketed. My doctor put me on BP medication, and any time I felt pain near my rib cage I worried: could it be my liver? Going in the day before meant I could relax, adjust to my new surroundings, and mentally prepare for delivery.

Day 0

Delivery day! My husband was present for the procedure, but had to leave immediately after. Basically he got to say to our son, “Hey, it’s me, your dad. See you in a few days!” Not a great experience for him, but better than nothing.

In the operating room I could see my husband on my left, and a clock on the right, so I knew how long everything was taking. I had been given the option (in a pre-op consultation with the anesthesiologist) to be sedated after I met Baby, while the doctor stitched me up. I asked her what most people did, and she said a majority opted to be knocked out. I almost chose that too, but then decided against it. I didn’t want to be in a fog at all that day; I had my fill with the first birth.

The first time I gave birth, I was not conscious for my daughter’s first breath, and my husband was not present. This time, we both heard our son’s first cry. It was a gift to simply feel joy in that moment. It contrasted with the stew of emotions I felt that first time: happy of course, to have a healthy baby, but also confused and scared and a whole host of other feelings too slippery to name.

As mentioned above, the hospital had rules around skin-to-skin contact in the operating room that I still don’t understand. I remember the nurse touched Baby’s forehead to mine. I wasn’t too worried about the prohibition as I knew I would be spending nearly every moment together with my newborn in the days and months to come.

After the nurse wheeled me back to my room, I was encouraged to sleep. The staff knew my preference for exclusively nursing, and reassured me that they’d bring my son when he was ready to eat. The top priority of Day 0 was my rest and recovery, and this was after a surgical procedure that went precisely according to plan.

Baby’s first photo! I thought he looked a little like George Costanza here, and I say that with love.

In contrast, after Birth #1, in which so much went spectacularly wrong, I was wheeled back to my hospital room, handed my daughter, and immediately instructed to breastfeed. When I wrote my first birth story, I concluded by saying that the American hospital failed me in the aftercare process, pretty much as soon as I had woken up from general anesthesia. I wanted to hold my baby, of course, and also wanted to attempt nursing—but it felt like a job was being demanded of me when I had never felt more physically and emotionally vulnerable. I had IVs in both my arms at that point. I had almost just died! Yet I was being asked to carry on as if none of that were part of my reality.

While I remember the harsh overhead lighting in the US hospital, the lights were turned off on Day 0 in my hospital room in Japan. It was quiet and calm when a nurse wheeled Baby Boy to me in his bassinet, as promised, after an undetermined length of time. (In a shocking turn of events, I may have actually dozed off for a while.) We had our skin-to-skin contact, he latched on, and all was right with the world.

Day 1

On Day 1, I had my scheduled “bath” with a hot towel. While this may seem like oversharing a minor detail, it underscores another important difference between my American and Japanese birth experiences. In the pre-COVID world, in the American hospital, it felt as if me, my husband, and my parents were chiefly responsible for my aftercare and the baby’s. One nurse asked me (One day after the surgery? Two?) if I’d been out of bed, and I said no, I didn’t know I was allowed. And frankly, I was confused about how I could, with IVs in both arms as well as a catheter. She huffed as if I’d failed a test and said moving was important for my healing. But no one had told me!

The same went for bathing. In the US it wasn’t clear when, if, and how this would happen. And when one of the nurses (an older, brusque one with short, curly hair) informed me it was time to shower, and to actually look at my stitches, I became agitated. I had a hard time articulating just how frightened I was to look at those stitches; I absolutely couldn’t, let alone “gently cleanse the area.” After I locked myself in the bathroom, she told my parents I was upset due to the pain, which was only partly true.

I don’t think my nurses in Japan were any better equipped to handle post-birth emotional trauma, but it was clearly communicated to me that I would have someone’s assistance on Day 1 to help with cleansing, and on Day 2 I would be expected to leave Baby in the nursery and shower by myself. Personal care and hygiene is an integral part of recovery, and that was clearly acknowledged.

Rest, Recovery, and Rooming In

In the American hospital, I was never encouraged to rest, or even if I was, it wasn’t a condition the hospital made possible. I clearly remember the pediatrician coming in at 3 AM one day and demanding to know when my newborn’s first post-hospital checkup was scheduled and where. I had no idea; and her attitude told me that I’d once again failed some crucial test.

I know everyone says they don’t sleep when a newborn arrives, chiefly because the baby needs to eat every few hours. But when I say I didn't sleep when I was in the hospital, I mean I was awake for several days straight. Even when my baby was sleeping, my body would not allow me to rest. I gave up even trying, and watched television. I became convinced I would never sleep until I was allowed to go home: to be in my own comfortable bed, away from judgmental doctors dropping in on me at 3 AM. At home, someone—a parent, my husband—would actually take the baby out of my room for an hour, unlike at the hospital.

Above: a drawing from my daughter; a typical tasty and healthy meal; the room.

The American hospital didn’t have a nursery. As part of a baby-first philosophy, all newborns roomed in with the parent. This could ease some mothers’ anxiety by having their baby with them every moment, but it only made mine worse.

Together Yet Apart

Although my Japanese doctor spoke perfect English, the nurses did not. I tried my best to speak the little Japanese I knew, and some of them tried their best with English. At one point, a nurse brought in an English-speaking concierge to translate for us. All of the nurses were equipped with pocket translators, which some relied on more heavily than others. The translations could be strange or comedic, so even my minimum understanding of how Japanese is structured helped in these situations. For more complex questions about my pain level or medications, I would text my doctor, who would then respond to me and/or communicate my need to the staff.

The fact that it was my second baby made my stay in a foreign hospital that much easier. Nursing, for example. I knew it was going to hurt those early days, and how much. I knew all about a “good latch,” so when a nurse roughly and wordlessly positioned Baby Boy on my very sore nipple, I could laugh about it to myself. I would have been so confused and probably horrified if it had been my first time.

In the US there were lactation consultants on staff who would visit my room once per day. I remember one consultant speaking to her trainee instead of directly to me.

“It feels like little knives when they latch,” she explained as I winced.

Despite this knowledge, the consultant showed little sympathy for me. Again, she was another examiner, frustrated at my slow progress and critical of my posture, as if the fresh wound in my abdomen should have had no effect on how I carried my body.

I am not sure if any of the nurses in Tokyo were lactation consultants—a few had knit boobs on keychains, which I assume (hope) they used to demonstrate proper latching technique. From my limited experience in Japan, nursing is encouraged, but it seems much more private than in the US. This was part of a larger dynamic I noticed during my hospital stay. Despite the maternity ward being a distinctly feminine space—my ObGYN was the sole male I encountered during his short visits—there didn’t seem to be a sense of comradery among the new moms. I did not expect anyone to connect with me—from what I could tell, I was the only non-Japanese person on the entire floor and my language skills were severely limited—but I did expect to see moms conversing in the common area, or openly nursing.

One morning, a few of us were waiting in the nursery to have our babies checked and weighed by the doctor for a pre-discharge examination. The room was occupied exclusively by health professionals (all women), babies, and moms. When my son began fussing during the wait, I nursed him then and there. The woman next to me shifted away to a further seat. We were literally in line to ensure that our babies were getting enough nourishment, and I was the only one to ever expose my chest (that I saw) outside the privacy of my room.

What a difference from Seattle, where I sometimes attended breastfeeding “office hours” at the hospital. The participants all sat around in a faux living room with our boobs out, frequently talking, sometimes crying. Sometimes a partner (often—gasp!—a man!) would attend; once I brought my sister (sorry, sis!). At least with all the pressure to nurse, we had an outlet to commiserate together.

Every person has their own comfort level, but I did feel sorry for any new moms in that Japanese maternity ward who didn’t feel free to openly feed their babies, especially if they were struggling. Again, it’s hard to tell how much COVID played a role in how isolated it felt. For example, we all wore our masks outside of our rooms, and I generally wore mine any time a nurse entered my room too.

Above: The patients about to head home. The morning I left I showered, dried my hair, and put on a dress. This was in sharp contrast from Birth #1, when I went home in the same clothes I arrived in, looking and feeling horrible.

Leaving the Hospital

After five nights and days that passed both slowly and quickly, I was cleared to go home. In the US, we could not leave the hospital without a proper car seat and a demonstration that we knew how to use it. In Tokyo, I saw women simply gather their infants in their arms, call a taxi, and get in. At least one did this by herself; the rest hailed cabs with their partners or family. We had our car seat ready to go, of course, for any Americans reading that last sentence and clutching their proverbial pearls.

It’s been several months, and I can say that I look back upon my time in the Japanese maternity ward with fondness. It wasn’t a perfect experience, but I felt well cared for. I feel a bit bad writing this—because my husband was stuck home worrying about his wife and newborn, and my oldest child was missing her mom—but it was cozy having those first few days alone with my new baby, with nothing to worry about other than taking care of ourselves. Home is wonderful and comfortable in its own ways, but it was nice that while my son and I were getting to know one another, I didn’t have to think about where the bassinet should go, or what we should have for dinner, or how my daughter felt about sharing the spotlight.

When people say how difficult it is to have and care for a baby, I think what we really mean is it’s near impossible without support. When it comes to childbirth, we spend an awful lot of energy on choices—judging others’ and agonizing over our own. Maternity home or hospital, vaginal or cesarean, formula or nursing—it all ends up mattering very little in the ultimate goal of raising a loved and cared-for human.

What will matter in the moment, and rippling out to the future and beyond, will be the support you receive. For others to first acknowledge, “I see you,” and then show up to help.